|

|

Panels

Home | Standard Version |

|

|

|

|

||

| The Improvement Infrastructure The Missing Link or Why We Are Always Worried About "Sustainability"... |

For decades NSF and other funders have invested in the improvement of math and science education, seeking to improve the quality of teaching and learning in the nation's 16,000 school districts. Their investments have pursued different strategies -- curriculum development, professional development, new assessments, systemic change and, now, most recently the newly created Centers for Teaching and Learning, and the Math Science Partnerships.

While these investment strategies vary in their purposes, foci, and approach, they all share a few common features:

In short, the NSF funds are intended to get bring in outside expertise, get "the ball rolling", and it is then up the state and local school system to "keep the ball rolling".

Now on the surface, it would seem that the most difficult part of the job would be to get the ball rolling. Districts have to find and hire expert professional developers; they need to identify, adopt and implement standards-based curricula; they need to align assessments with their goals, and they need to create an administrative and public context that is supportive of a new vision of teaching and learning. And given the very limited funds NSF has available, and given the scale of the system, one would think that it would be hard for NSF to make any inroads into the systems it works with. And, conversely, one would also think that the state and local systems, with many more resources would be able to continue to fund, on a much larger scale even, the programs initiated through NSF funding. They could continue to hire professional developers, coaches, curriculum specialists, assessment people so that promising programs started with NSF funds would not be lost.

So you would think it would be hard to get the ball rolling, but relatively easy to keep it rolling once it got started. But the opposite often seems to be true. It is, I am afraid to say, a very rare occasion that we see strong examples of programs that are "institutionalized", and projects that are sustained and expanded beyond NSF funding. The NSF funding may very well bring about supportive activities that provide infusions of professional development, new curricula etc into a school district. But it is less often that states, districts and schools are able to extend and build upon that work.

And the natural question to ask, then, is why is this "sustainability" so apparently unachievable?

The current focus of educational improvement efforts is clearly centered on the assessment of "student achievement". Student achievement, it is said, is the "bottom line" of schooling. And to improve education, it is argued, we must hold schools and teachers "accountable" for the student achievement of the students that they work with.

The nation currently, in fact, is placing all of its "bets" on an improvement strategy that centers around the logic of accountability. The bet is that if we measure student achievement, however insufficiently, and hold local systems "accountable" for those results, then we will provide both incentives and guidance for local school systems so that they can and will improve the instruction they offer --and improved student achievement will result.

Following a kind of corporate or industrial model, the idea is that by focusing solely on test outcomes (profits), we can reform the ways in which schools (companies) function. The idea is that you can re-shape the process of education by focusing on outcomes --- that clear assessment of outcomes coupled with appropriate incentives will drive people to improve what they are doing.

I, and many others who work in schools, question this fundamental logic. Our own work as evaluators have shown us many shortcomings and unseen costs of the accountability movement. (In industry Deming and others have pointed out the dangers and failures of high-stakes outcome-based accountability systems.) There are many reasons for my skepticism about the long term benefits of the accountability strategy; in particular, I want to point out that the mechanism for improvement is not well-specified in the accountability logic. Rather there is a kind of pride in saying; "we will lay out the goals; it is up to you to figure out how to reach them."

It is important to examine closely some of the implicit assumptions that seem to under gird the logic of accountability and the investments that are made to set and achieve high standards. For example, what are the implicit assumptions the accountability movement makes about the causes of what is seen as inadequate performances of districts, schools and teachers? Does not the accountability strategy assume some sort of lack of focus, laziness, or even negligence? ( This things may well exist, but are they really the core reason for the failures of the current system?) Is there not a basic underlying punitive attitude toward schools and teachers in this stance? (It is interesting to note that the current administration talks of holding two groups - terrorists and teachers - "accountable" with much the same tone! ). Can we really use standards, assessments and accountability to "whip people into shape"?

Perhaps, let me suggest, that there is a more basic reason that districts, schools and teachers do not improve the instruction they offer students. And that is that they can't. Districts and school simply lack the knowledge, resources, time, mandate and expertise to carry out a process of instructional improvement.

In fact, I think that there are three underlying reasons that systems (education, legal, medical) do not improve themselves, and do not successfully adjudicate their shortcoming . These reasons can be summed up as Capacity, Constraint, and Confusion.

Hence, we have state and local school systems that lack capacity, face constraints and suffer from confusion! (And we are wondering why our projects and programs which are started on soft money are not sustained).

It is interesting to note that many current and proposed reform strategies seek to address these issues. Charter schools, for example, are proposed as a way to eliminate many of the current constraints. Vouchers are seen as a way to let parents and students vote with their feet about what they see as "good" schooling. Accountability is in some ways an attempt to come to agreement about the purposes and measures of good schooling. Few current reform proposals directly address what I think is the most critical of the Cs -- the Capacity for Improvement.

Lasting instructional improvement seems highly unlikely unless districts and schools themselves have the internal capacity to improve their own instructional programs in an ongoing sustainable fashion.

There are industries that are able to continually improve themselves. Software makers, drug companies, computer companies, aircraft producers and car manufacturers are all engaged in a constant serious effort to improve their processes and products. They invest in this capacity in a thoughtful serious fashion. Why are these industries, which largely focus on products as opposed to social services, so different from education in this regard?

One reason I would argue is that they all understand the need for, and invest heavily in what has been called their "improvement infrastructure". Just as infrastructure (electricity, bridges, water, airports etc.) supports the functioning of the society, an improvement infrastructure supports the maintenance and continual upgrading of the infrastructure. The improvement infrastructure maintains the safety of the bridges, it assures the quality of the water, it designs the next generation of airplanes, it explores new software products...

Industries recognize the need to establish and fund their own improvement infrastructures. That is, software makers invest not only in making, producing, marketing and distributing their product - but they also invest heavily in continually improving their products (hard to believe sometimes, I know...). Similarly, drug makers spend huge amounts of money on research and development and on building their own capacity to conduct high quality research and development. Aircraft designers like Boeing build incredible aircraft, and they also spend significant amounts of their overall revenue in maintaining quality and improving the quality of the design and construction of their planes. They invest heavily in their own capacity for ongoing improvement. They do NOT assume that the people who do the business will necessarily have the resources and the expertise to ALSO be able to improve the doing of the business. Nor do they rely entirely on outside intermediary organizations such as federally funded research labs to do all the research and monitoring that is needed.

In education I think there is almost no improvement infrastructure. There is not even a conception of such a thing, or the need for such a thing. Very few states, districts or schools invest significant amounts of their own money into developing and maintaining their own ongoing capacity to improve their own instructional programs.

Microsoft spends something like 16% of its considerable revenues on research, development and other improvement efforts. Kodak was recently criticized in a business magazine for spending only 6% of its revenue on its R&D. Typically, progressive companies spend on the order of 10% of revenues on improvement.

In our educational system, by contrast, the resources and expertise for improving instruction lie outside the system. And they are supported almost entirely by "soft money" provided by foundations and government agencies. The improvement infrastructure for education resides almost entirely in intermediary organizations - these are the institutions, agencies and people that are funded to be the "partners" who work with schools and districts to improve instruction.

The investments a company makes to improve itself do not go to the same people who are busy running the company and producing the product. There is a different expertise required to improve the product and production process, than the skills needed to operate the company. Hence, there are two types of jobs that exist within the same company; they are very distinct, have different purposes, are evaluated differently -- and both are more than full time.

Those educators who are involved in reform and who are reading this little essay will no doubt understand why I have emphasized this point. In education we assure that we can provide money (or not even) to people who are running the schools and that they will have the time, expertise, and incentives to take on the second job of improving schools as well as running them. This phenomenon is often described as trying "to change the tires on the car while it is moving."

Think even on the surface level about the logic of funding people working in beleaguered school districts to engineer their own instructional improvement. Funders want to assist students who are disadvantaged and low achieving. Most often these students reside in urban and rural districts that have serious problems. The administrators and teachers in those districts are already overloaded and struggling -they are working as hard as they can to improve student achievement and are being overwhelmed by the multitude of challenges they face. And then the funder offers them money, saying "Here is more money and we want you to use it to conduct a serious and rigorous reform effort. We want you to take on the additional even more daunting challenge of fundamentally reforming your vision of teaching and learning, and thereby greatly improve the quality of teaching and learning that takes place in your schools." What makes us think that a group of people who are already stretched thin just running the schools has the time, expertise, and resources for doing the work of reform?

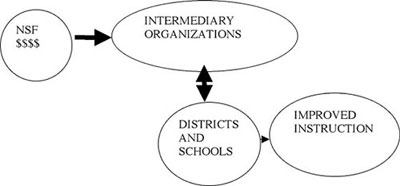

The chart above illustrates the current situation. NSF and other funders provide funding to intermediary organizations who seek to partner with the schools to bring about needed improvements. But who is available within the school system to do the work? With a few exceptions it is only the administrators and teachers who are already working full time. There is in some deep sense "no one home."

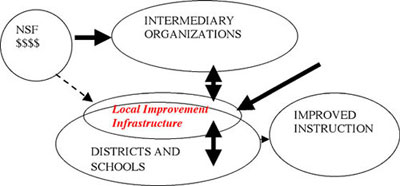

Now consider an alternative scenario as illustrated in the chart above. Suppose that a strong local improvement infrastructure existed. By this I mean that the district itself invested in permanent positions for professional developers, coaches, curriculum specialists etc... And that these people were available to work with 1) the intermediary organizations who have the expertise to bring to bear, and 2) with the local administrators and teachers who are responsible for all of the instruction within the district. This would greatly enhance, I am arguing, the effectiveness of investments made by NSF and other funders, and it would make real the possibility that short-term investments could yield long term sustainable results.

The local improvement infrastructure is the missing link. It is the interface that is now missing between those who work in intermediary organizations and those administrators and teachers who are responsible for delivering instruction.

Now do not misunderstand... I am not arguing that principals and teachers should be left out of the effort to improve instruction. Not at all. But I am arguing that they can never succeed if they are not supported by a strong local improvement infrastructure that is of a scale and type similar to that found in other industries. They can never succeed if they alone are responsible for carrying out all the work of improvement. And I am also arguing that the improvement infrastructure can not reside solely in intermediary organizations such as museums, labs, universities etc. It must be a recognized distinct and permanent component of the school system.

Let me illustrate what I mean in another way. Take a school district that is about the size of the Seattle school district - approximately 60,000 students and an annual budget of approximately $400 million dollars. Let say that we decided to spend 10% of that revenue on an improvement infrastructure. That is, $40 million dollars per year would go to people, resources, and capacities that would be solely focused on maintaining and improving the quality of classroom instruction. Not on doing instruction, running the buses, paying teachers etc... But on people, resources, and processes that will support administrators and teachers in ways that allow them to improve the quality of instruction offered to students.

Now let's say that half of that improvement infrastructure money ($20M) is for elementary education. And let's say that one -seventh (not a very generous portion!) goes for elementary science. This would provide nearly three million dollars per year - every year -- to support (improve) elementary science education in Seattle. That $3M per year is approximately twice the current funding level of their elementary science LSC. These improvement infrastructure funds could provide for curricular improvement and support, kit maintenance, professional development sessions, teachers on special assignment, building coaches etc. The funds could support a science team indefinitely doing the constantly needed work of program improvement and maintenance. (Last year I wrote about the painting crews on the Golden Gate bridge who are hired full time to simply keep up with the ongoing processes of erosion. In a similar way instructional programs face serious processes of ongoing erosion.) If we were able to recognize the need for an improvement infrastructure, and if we could fund it with permanent and not temporary funds, then there would be an ongoing capacity for the continual improvement of elementary science education in districts like Seattle.

Even a 5% expenditure on the improvement infrastructure would provide for a level of support equivalent to an ongoing LSC in every subject area. And then the NSF initiatives would have something to work with. The initiatives could then support the growth and development of the elements of the local improvement infrastructure. And the residue of the NSF programs would reside in the enhanced improvement infrastructure. And the question of sustainability would disappear, or at least be addressable.

But is this possible? Could a district really find these monies? I would argue yes -- but not without major RE-CONCEPTUALIZATION.

While I do not know his work well, I believe that in some ways this is what Tony Alvarado did in District 2 in New York and continues to do in San Diego. In District 2 professional development expenditures went from less that one percent to over six percent of the budget. To do this he has made massive changes in the conceptualization of district administrator roles and structures, and has accordingly reallocated how funds are used. The point is not whether you agree with Tony Alvarado's approach but rather I want to cite this example as two feasibility proofs that show it is possible for districts to re-conceptualize their expenditures, and to include in their thinking, a significant ongoing investment in a local sustainable improvement infrastructure.

And, again, I argue that this idea of a local improvement infrastructure is the key to the long term value of the investments that NSF and others make in education. The lack of such an infrastructure, and the failure to even conceptually recognize the possibility and need for such an infrastructure, will continue to limit to a very great extent the benefits of outside funding. (In fact, one might even argue that states and districts have come to rely on soft money and an endless string of projects to supply what little improvement infrastructure they do have.)

Hence, I would propose that we all look more seriously at how schools are funded, and how those funds are used. I think we need to recognize the need for a significant ongoing locally supported improvement infrastructure. (It would be an interesting experiment for a state to designate that 5% of all state funding to districts be used only for the development and support of their instructional improvement infrastructure. The state would then monitor and evaluate the investment not on the basis of student achievement but rather on the basis of creating expertise and resources that continually support the improvement of instruction.)

I and others could argue that NSF and other funders do a very conscientious job of investing their funds. But I would also argue that their success in improving local schools and districts will always be limited by the absence of this missing link. If I were able to give a million dollars tomorrow to each and every school district it would do little I believe to improve the quality of instruction. (It would be like giving a large steak to a person who has been starving for many years; they simply have lost the ability to absorb that much nourishment.)

Thus, I think there is good news and bad news in what I have to say. The bad news is that we are unlikely to use externally funded programs to make sustainable improvements in math and science education until we recognize the need to invest in a special kind of capacity in an ongoing manner in all of our schools. And there still remain the other 2 Cs - constraints and confusion - which must be dealt with. But the good news is that maybe we are close to identifying a missing link in our improvement strategies, and we can begin to address that missing link directly.

|

|

|

|

|